After the declaration of Independence, Finland elected its first – and last – monarch. His great-grandson is a photographer in Germany.

By Camilla Alfthan

‘Väinö the First’ was the nickname of the prince who in 1918 became Finland’s first monarch – a name inspired by Väinamöinen; the hero of Finland’s epic Kalevala tales. His real name was a little longer – Charles the first, King of Finland and Karelia, count of Åland, Grand Duke of Lapland, Lord of Kalevala and the Nordics. An impressive row of titles for the man elected ruler of Great Finland.

The story, however, turned out differently and the monarchy was abandoned after just two months, before the new king had even set foot on Finnish soil. Though Finland’s short-lived flirt with monarchy is now a colourful interlude in the nation’s turbulent beginnings, the king is not entirely forgotten.

In Helsinki the House of Knights recently opened an exhibition about his two months on the throne. Guest of honour was the German prince Philipp of Hessen who today could have been king of Finland had his great-grandfather remained in this position.

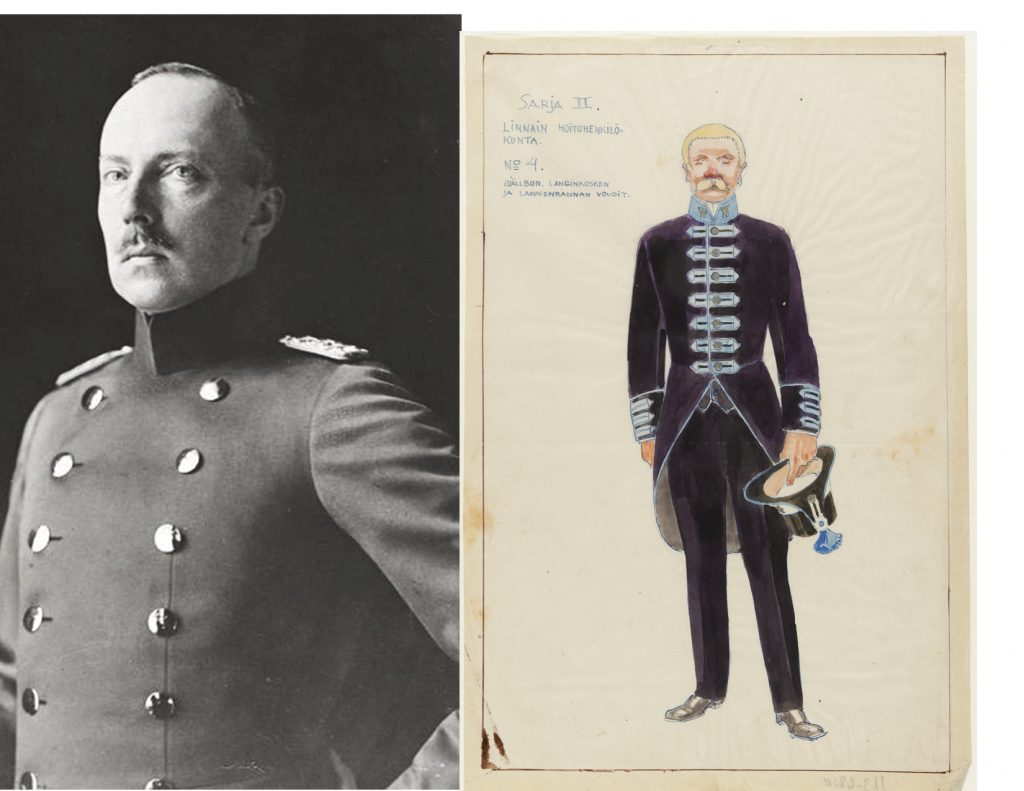

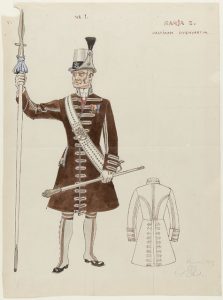

The exhibition displayed the impressive speed with which the Finns began to create their own royal house. Letters of nobility were written and a crown was drawn, while the famous painter, Akseli-Gallén Kallela designed uniforms for the employees of the court.

The Imperial Palace which was built during Finland’s years as an independent Russian duchy, was going to be transformed into a royal castle after a thorough renovation following the devastations of the civil war where the red guards had used it as their headquarters.

An architect and an interior designer of the department store, Stockmann were hired to decorate the king’s private residence – an impressive villa in the Eira district by Gustaf Estlander which had been completed by the famous Finnish architect, Eliel Saarinen. They drew detailed plans and travelled to European cities to buy furniture, mirrors, lamps, silver wear and porcelain. Much was German biedermeier – the height of fashion at the time. Nordic touches were Finnish ryas and Gustavian cupboards.

“The election of the king was a strategic decision as the Finns wanted a monarch as a counterbalance to the Russian dictator. They first asked the German emperor if they could have one of his sons but he declined and suggested his brother-in-law, Friedrich Karl, who was a prince and Landgraff of Hessen, “ tells his 47-year old great-grandson, Philipp of Hessen.

King Charles the First of Finland and his valet. Uniforms for his employees were designed by the famous painter, Akseli Gallén-Kallella. © Museiverket.

King Charles the First of Finland and his valet. Uniforms for his employees were designed by the famous painter, Akseli Gallén-Kallella. © Museiverket.

World War I was raging in most of Europe and a revolution had broken out in Russia. When Finland left the crumbling Czarist regime, the country was suddenly divided in two : The official White Finland which had declared its’ Independence and the Reds who wanted to join the new communist state. During the brief war which followed the Vasa government began to discuss a change in Finland’s constitution.

“The Russian revolution had spread to Finland and the bolsheviks encouraged the social democrats to take up arms. When the Soviets recognized Finland’s Independence on New Year’s eve 1917 it was only because they thought that the social democrats would take power,” tells historian Henrik Meinander.

The Germans became an important ally against the bolsheviks as Finnish soldiers who had been training in Germany – the chasseurs, who came back with their German brothers-in-arms to fight in the civil war. Only 11 days after their arrival at the coastline of Hangö they marched into the capital and declared victory even if the final battles did not end until one month later, on May 15th led by the legendary general Mannerheim.

»The alliance with the Germans helped secure Finland’s independence and the idea was that a monarchy would do the same even if the Finnish law did not quite allow such a change in the constitution. So they chose a form of government from 1772 when Finland was a part of the Swedish monarchy,” tells Meinander.

The Duke of Mecklenburg was among the candidates to the throne. Friedrich Karl of Hessen was a candidate and a sceptic, wishing that the entire Finnish population should support his candidacy. The Danish Prince Axel who was an admiral in the royal navy was also briefly mentioned. The German pressure was strong and the opposition had a hard time being heard, just as the advocates of a Swedish candidate.

“If they must have a king they can take the prince of Wied-Albania who is used to being removed and used to the idea that a bullet is already cast for him. They should understand that a bosch king in the year of 1918 won’t be long-lived,” a Finnish diplomat in Paris wrote ironically.

A Bosch king, a German, was nevertheless elected on October 9th when the Landgraff of Hessen was chosen with a small majority, despite the fact that the social democrats had long fled the country or been imprisoned.

The crown as a sketch. A Finnish jewelry company later made a replica.

The timing, however, could not have been worse. Only a month after Friedrich Karl’s election Germany lost the war and their own imperial rule was abruptly put to an end. None of the Western victors had an interest in recognizing the German king and the course was subsequently changed. The king was no longer going to be invited to Finland, the government had to step down and politics should no longer be based on friendly turns.

On December 14th Friedrich Karl retired after just two months on the throne. General Mannerheim became head of the national assembly and the Finns chose their first president, the lawyer K.J. Ståhlberg. As a republic the country ended up with a modern, an entirely different identity, which was in line with the constitutional changes of 1906 when the nobility lost its power and women the following year could run for parliament as the first in the world.

“When the Norwegian monarchy was born in 1905 it happened under completely different and calmer circumstances, and with help from the Danes. In theory, a Finnish monarchy could have worked as a counterbalance to the revolution. The Russian empire had vanished but the Austrian, German and Osmanian monarchies were still the main governmental form, so the idea wasn’t completely wrong. It is only now that we can see things in a different light,” says Meinander.

When Finland celebrated the centennial of their independence, the king’s great-grandson was not invited “if I should try to take power,” jokes Philipp of Hessen who spent the day in Spain with his wife Laetitia and their three children.

The first time the prince was invited to the cold north by the people who could have been his Finnish subjects, he was 32 and a photographer assistant in New York. The newspaper, Helsingin Sanomat had invited him to the capital in a ‘what-if’ experiment as King Väinö. With photographers following his foot steps the king visited kindergartens, and met with cultural personalities and he was even photographed in front of the czar throne at the National Museum, which is the only existing throne outside of Russia.

“Today monarchy has changed. The royals are representatives for their countries and a continuation of their long histories. They are also fantastic for tourism – like a corporate identity!”

A few years ago prince Philipp moved from New York home to Hamburg where he works with his wife in her online company, Niche Beauté.

“ I grew up in Germany where there’s no longer a monarchy so I’m quite happy with the way things turned out. The Spanish royal house, the Dutch and the Danish – they are all good friends,” tells the prince who has just been to Denmark to visit Prince Joakim. The Greek king is also a relative.

“Somehow we’re all related,” laughs the prince who has photographed some of his blue blooded relatives for the American magazine, Vanity Fair.

The Finnish chapter is one of many flamboyant tales in his family, which includes Sweden’s King Fredrik who ruled in the 1700s and who was also Landgraff of Hessen.

Friedrich Karl’s wife, Princess Margaret of Prussia, a grandchild of England’s Queen Victoria, gave him six children. When the eldest two sons died in the First World War and the following heir to the throne did not have any children Philipp of Hessen would have been next in line.

“Instead he had a crazy life! From being a member of the Nazi party to becoming a prisoner of war and losing his wife in a concentration camp. I was ten when he died so I never got to ask him about his life,” tells the prince about his grandfather and namesake.

The gap between being a monarch and working with images is not as wide as one could think.

“Today monarchy has changed – it is completely different than in the old days. The royals are representatives for their countries and at the same time a continuation of their long histories. They are also fantastic for tourism – like a corporate identity. The Danes have made millions with Queen Margrethe,” tells Philipp of Hessen with a laugh.

When the Finnish monarchy was cancelled, the king’s treasures were sold at the department store, Stockmann. Some of the furniture was bought by the publishing tycoon, Amos Anderson. The would-have-been royal castle, became the presidential palace and the king’s grand villa was sold to Italy who still use the building as their embassy. In Kemi in Lapland where gold washers still find real, Finnish gold a jewelry company has made a copy of the crown which is exhibited as a curiosity. ©

“King for two months” is exhibited at the Museum Milavida in Tammerfors/Tampere from February 9th – October 28th. At the National Museum in Helsinki ‘The story about Finland’ shows the country’s transformation into an independent nation.

Uniforms for the employees at the court – a fisherman from the former Imperial fishing lodge at Langankoski, Eastern Finland and a driver. © Museiverket